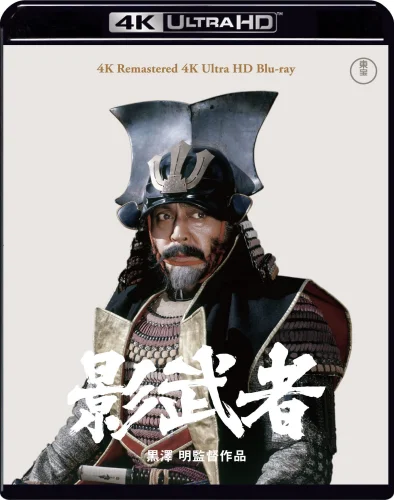

Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior 4K 1980 Ultra HD 2160p

In the 16th century in Japan, a thief was spared because he looked very much like a prince. It was decided to make him a double for the ruler because the throne was threatened by numerous enemies.

User Review

Did Stalin, Hitler, and Mao have doubles? According to Kurosawa, the outstanding 16th-century Japanese military commander Takeda Shingen did. Shingen spent his entire life on the battlefield, earning the respect of his enemies and undying glory from his descendants; sometimes he needed to be in two places at once — and a doppelganger he found by chance came in very handy for this purpose. He was an ordinary thief and a rogue. Not much was required of him — just to sit with an important look on his face and roll his eyes menacingly. But Shingen suddenly dies, and his enemies are ready to unite — to save the Takeda clan, their leader must remain alive! So a beggar becomes a prince; a rogue becomes a warrior; a loner becomes the head of a large and noble family. Will three years be enough for him to understand what it means to be Takeda Shingen, what it means to hold his grandson in his arms, what it means to lead samurai into battle and see them die protecting you? And if he does, what will happen to him when he has played his part?

Three things admire me most about Japanese culture: the samurai code, the fascination with transience, and the poetic attitude toward life. The samurai's maxim is very simple: “If you strengthen your resolve to die in battle every day and live as if you were already dead, you will succeed in your endeavors and in battle, and you will never disgrace yourself” (Yamamoto Tsunetomo). This resonates with the concept of mono-no-aware: “If human life were eternal and did not disappear one fine day like dew on the Adachi plain, it would not have so much hidden charm” (Yoshida Kenko). What else is such a life like if not a death poem? Uesugi Kenshin, wielding his sword, fought his way to Shingen and asked him what he was thinking before his death. Shingen composed an elegant haiku and parried the blow with his battle fan. “Everything is beautiful, like a dream. Dreams come and go. Our life is a dream within a dream.” Did the thief Kagemusha understand this?

Three things impress me most about the film Kagemusha: the colorful banners on the battlefield, the transformation of the main character, and the aesthetics of Noh theater. In the West, a simple warrior is a pawn, but in the East, everyone is a standard-bearer. Each banner is almost personal: a clan symbol, a troop color, a motto in hieroglyphs. You die with it, you don't abandon it. It's no surprise that the samurai spirit came alive in our thief. It was as if one Noh mask was replaced by another. And then another, and another, until we ended up with a red-eyed, half-mad shivazero. In fact, not only the hero, but the entire film follows the canons of Japanese theater: whether it be the roles — a man and his ghostly shadow — or the music — the indispensable drums and flute — or the individual scenes and overall composition (the classic jōmonō — a play about the trials and tribulations of life). And it comes as no surprise to see Oda Nobunaga, another great military leader and prince in the film, performing a dance with a fan upon receiving news of Shingen's death. His strange movements clearly convey respect, joy, and a sense of impending change.

Three things admire me most in Kurosawa's work: his partnership with Toshiro Mifune, the master's special attention to world culture, and his truly Shakespearean dramaturgy. Mifune is not in Kagemusha, but there is plenty of epic drama, strong characters, and all-consuming passions. This film is similar to two other Kurosawa masterpieces, Throne of Blood and Ran, but unlike them, it is based on original material rather than motifs from Shakespearean tragedies. Perhaps it was in Kagemusha that the master reached the height of his tragic talent, creating not a samurai canvas, but a universal one. It is no coincidence that there is not a single samurai duel in the film, and we can only read the results of the battles on the faces of the participants. The story of a cynical thief who suddenly discovers other, much higher values and meanings, thereby radically changing his fate, is worthy of standing alongside the story of a traitorous regicide or the three daughters of an unfortunate king. I don't think it would be too bold to call Kurosawa, along with Chekhov and Shakespeare, the Shakespeare of the 20th century. The Cannes branch of Kagemushi is just further proof of that.

Info Video

Codec: HEVC / H.265 (53.0 Mb/s)

Resolution: Native 4K (2160p)

Original aspect ratio: 1.85:1

Info Audio

#Japanese: DTS-HD Master Audio 4.0

#English: Dolby Digital 2.0 (Commentary by Kurosawa scholar Stephen Prince)

Info Subtitles

English, Japanese SDH.File size: 70.15 GB

Like

Like Don't Like

Don't Like